There was no reason to travel to the Amerika Haus when I lived in Berlin. This was from 2001 to 2008, and the beating heart of all that was interesting was firmly in the east — in the immigrant and anarchist neighborhoods of Kreuzberg, the rapidly gentrifying but still wonderfully sinful Mitte and Prenzlauer Berg. (Update: Mitte and Prenzlauer Berg fully gentrified; Kreuzberg virtually unchanged).

Amerika Haus, an elegant postmodern building that served as a cultural outpost in postwar Germany, stood by the elevated train tracks of Zoologischer Garten. Besides the Zoo, that area was best known for its junkies. One in particular — Christiana F. — cemented its troubled reputation.

But the pendulum swing of modern city life has brought vibes back to the West of Berlin. There are notable bars and restaurants there. And in 2014, one of Europe’s best photography exhibition venues — C/O Berlin — moved into Amerika Haus (the Amerikans having moved out in 2006).

It was there my old friend Pepe and I journeyed during a long-overdue weekend in the city. I was keen to see the first ever exhibition of the Instagram image-maker Sam Youkillis. The native New Yorker has 738,000 followers to whom he serves up perfectly formatted, algorithmic-friendly European summer delights and beautifully lit food “content” from elsewhere in the world. His work is accessible and aspirational. Each post gets hundreds of comments. He is loved.

The transition from 9:16 to the physical environment intrigued me. I was reminded of the hotly debated journey street artists went on, when they moved from the sides of buildings to gallery walls.

Beyond the question of whether the work would translate, I’ve been thinking a lot about the creative constraints of storytelling on the Internet; of work being governed by the stipulations — in format and content — of a handful of tech companies south of San Francisco that have taken our behaviors and created platforms that optimize them for rapid, frenetic consumption.

Creative expression has evolved along with every major technological invention — from the printing press, to Marconi, to film and television. But those mediums haven’t set forth the same biological change in us. Rarely have those leaps forward hacked our behavior and attention spans as violently as social media.

“You end up with whatever someone's weakness is in their brain being exploited by algorithms that the people who work at these companies don't even understand, to create addictive patterns and compulsive patterns. Because, if you're running a business, you want predictability, and the most predictable thing is addictive behavior.” - BuzzFeed Father Jonah Peretti on Brian Morrisey’s recent

The Rebooting podcast

This newsletter is about brands telling stories. Beyond product, and their retail spaces, there are few digital alternatives for them to do that beyond TikTok, Facebook, YouTube and Instagram. In the last few years, they’ve worked with creators with bigger audiences on those platforms to do the messaging for them. I wanted to see one of that group’s more artful practitioners, one that luxury brands from Prada to Jacquemus have sought out.

So, after a pallid currywurst around the corner, we walked in.

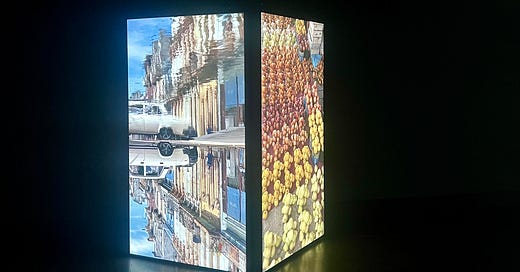

On more than a dozen large screens placed vertically, Youkillis’ scenes were presented in loops that went on for 6 minutes and then suddenly went dark at the same time. The choreography always managed to elicit a murmur of delight in the dozens that crowded the three-room space.

The vignettes themselves were pleasant. He uses lighting well and lingers long enough to capture moments: hands finding each other or arms wrapping as two people lean in for a kiss. On other screens, coffee is being made in Rome, olive oil being pressed in Tuscany; school children are walking to school, and swallows circle in formation.

There is no notable technical skill on display, or any perceptible artistic point of view beyond capturing pleasant moments. That’s why it works. He elicits in us a feeling that, by paying enough attention, we too could do this.

But it felt odd in a gallery. Strangely exposed.

I thought immediately about social media’s stranglehold on creative expression. That it’s no longer the medium, but the algorithmically optimized distribution that dictates the execution of the work. And, removed from the small screen context, it looks bland AF.

To what degree has the algorithm changed our visual expression? If Youkillis had chosen to capture something less universal than the pleasantness of one extended summer vacation, would the algorithm have rewarded him?

Would his work reach millions? Would the C/O Gallery have hosted him?

Compare that to an exhibition happening at the same time in Amerika Haus, down one flight of stairs.

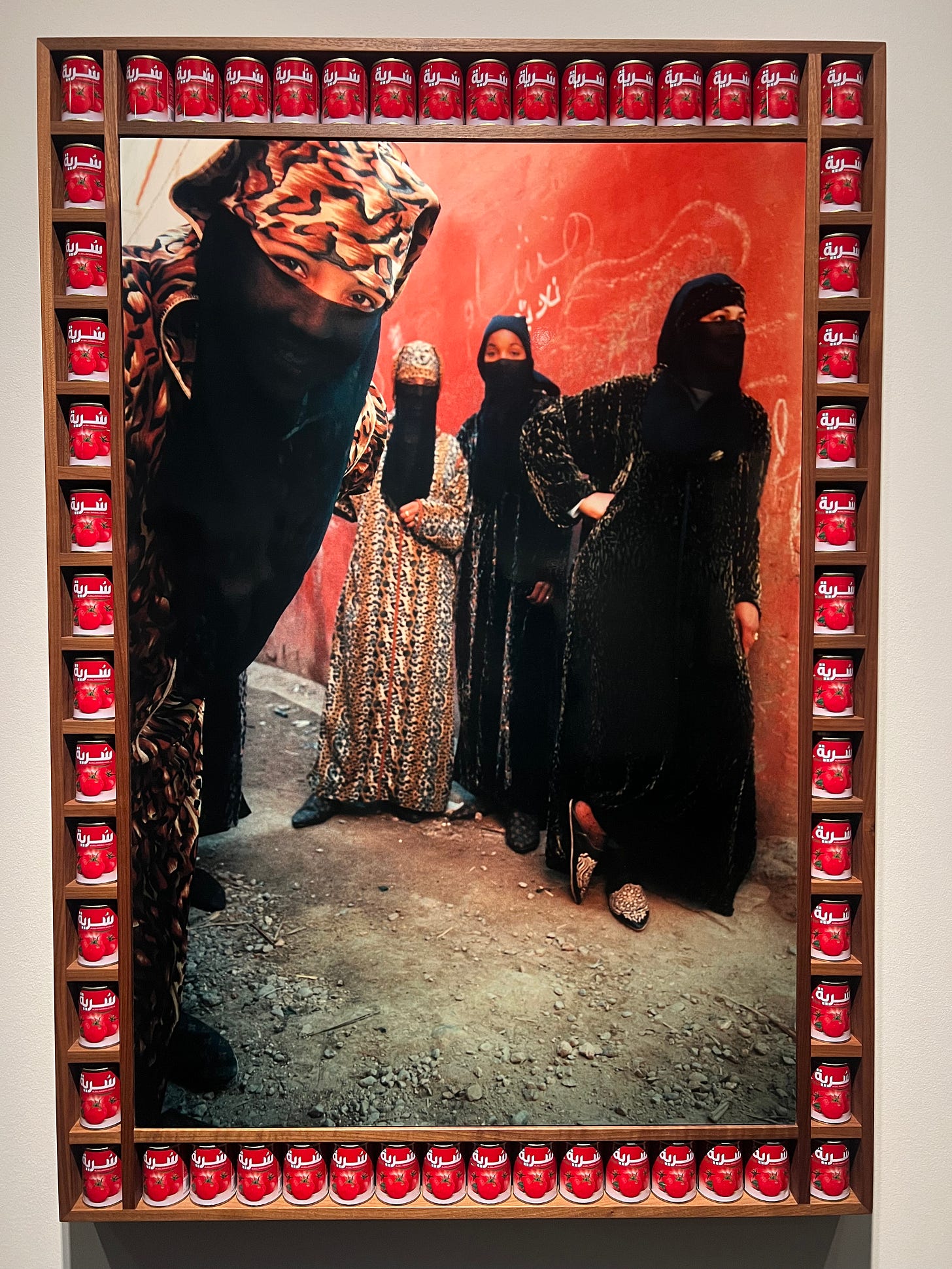

“A World in Common: Contemporary African Photography” featured the continent’s best and brightest, a stunning display of craft, joy, history, and pride.

Look at Hassan Hajaj’s “Kesh Angels”, in their djellabas and veils, looking very much like a 90s hip hop album cover as they tweak our perceptions of Muslim femininity. Each of his photos had a bespoke frame like the one above, with little shelves of canned goods featuring bright, eye-catching graphics. Hassan’s quote in his bio around the work: “I wanted to show what I saw of the country and its people: the energy, the attitude, the inventiveness and glamour of street fashion.”

Or the stunning, David LaChappelle-esque staged portraits of Fabrice Monteiro, whose “The Prophecy” series calls attention to the outsized burden African countries bear for our deteriorating planet. Each model is dressed as one of “mother nature’s spirits”, in clothes created from refuse found in landfills.

The works from 23 artists transported us. And in curating them, C/O Berlin did what museums are supposed to do: Lead us to unexpected, unfamiliar places, make us question our context, and widen our view. When’s the last time you could say that of social media.

There is a sobering backdrop of cultural budget cuts in Berlin at the moment (more than €130 million slashed from the 2025 budget). The city’s institutions need crowds. And Youkillis fits smoothly into that strategy.

But his kind of work already dominates our attention spans, available at any moment (how many times have I checked my feed since starting to write this?). What is the added value of a five-month run in one of the more visited photography spaces in Europe. And what other artist’s work is shelved as a result?

Youkillis’ pictures don’t demand we question much beyond when we might book our next vacation, or shift our perspective even slightly. And that’s really what this idea of art in buildings is all about. They are the last spaces that are curated — not in the algo sense, but by humans keen to provoke thought in other humans. As a result, they become bulwarks against the homogenization of creative expression.

The pieces that appear there take months, sometimes years to make. An investment of serious human capital, creativity and ingenuity. Would they make you stop your scroll? Maybe. But social “storytelling” rewards volume and pace. They couldn’t hope to keep up.

So — after that slightly protracted inner monologue of existential dread — let’s get to the Brand role in all of this, why don’t we. What efforts can they make to create memorable storytelling, beyond those cynically run social platforms?

Maybe they can spend less time partnering with established creators who’ve mastered the banality of social media vernacular and spend more effort in elevating surprising, unexpected voices. Backmarket did this with multidisciplinary artist Gab Bois recently, bringing out an eye-catching limited edition collection made of recycled consumer electronics.

They might treat social storytelling with a bit more experimentation, and weirdness — like PeopleCarePlanetCare.

But, really, if they can, they must find spaces beyond The Feed to build their universes: think better about how to utilize their retail footprints, make their owned platforms essential parts of their customer’s journey and seek out collaborators and “influencers” who’ve disrupted platforms. MSCHF’s Instagram feed could be shut down tomorrow and they’d still get tens of thousands clamoring for their limited edition drops.

Brands are already being asked to re-evaluate how they make things and radically minimize the harmful effects on people and planet. Thinking more carefully about how to tell stories beyond the wildly addictive platforms that dominate our discourse seems like a natural next step.

This is a forward-looking, inspiring piece. Thank you Dre!