A couple of years ago, I was in the bowels of London’s SoHo Hotel in front of a room full of Gen Z retail folks. Next to me on a small stage was Moses Rashid, the founder of The Edit LDN, a sneaker marketplace.

I’m not quite sure how I got there. I was only then starting to emerge from my post-Apple fug. It takes time to figure out who you are again after spending time at a big company. At least that’s been my experience. But the invitation to talk at something called Rarely Heard Voices appeared through a fairy godmother mentor of Heidi’s (and friend-of-the-letter, I think) called Liz Heller, and so there I sat.

I rambled a bit about bricks and mortar storytelling before focusing on his gig and we spoke a good amount about carving out a premium position in a crowded category.

The Edit LDN is a white glove sneaker resale business that Moses started in the pandemic and grew quickly. He’d managed to attract premium resellers with a proprietary tech stack that enabled them to immediately understand the margins on the sneakers they were putting up for sale. For instance, the Edit would suggest the price on a pair of Travis Scotts, using historical sales data and current market tracking (AI, obvs).

But his differentiation was really in offering a premium service: beautiful visual merchandising, sourcing hard-to-find items, even personal shopping. Success in that brutal category depends on relationships: with premium resellers or the brand management teams supplying you before the items release, and with a loyal set of sneaker enthusiasts willing to shell out top dollar for exclusive drops.

Moses would also figure out ways to get his brand aligned with other top-shelf retailers (a sneaker exhibit at Harrod’s) and top-shelf clients. NFL and Premier League players were ambassadors and investors. He raised a seed round of $4.8m in 2023 from a NYC-based private equity firm with an eye on expanding to the U.S. and other markets that would allow him quick shipping.

But the sneaker resale market underwent a brutal shift in the last few years, the follow-on effects of inflation and big brands like Nike oversupplying the market. Resale wasn’t fetching the margins it used to (StockX and GOAT anticipated this by expanding beyond shoes). A digital retail platform called Brand Alley (why not something equally shit like Brand Plaza? or Autobahn?) bought the Edit in 2024. Moses is now marketing director at UK-based retailer TOPSHOP.

I’m not sure better storytelling would’ve helped The Edit thrive in what has been a difficult economic climate. Their core customer will always rate them on their ability to source hard-to-get items and provide a luxury experience in the purchase process. Their investors will judge them on their ability to maintain operational efficiency while expanding into a big market like the United States. But perhaps a better and more consistent content strategy would’ve increased their addressable market, turning them into a trusted companion and guide to those who might have bought later down the line.

Below, two marketplaces that have taken this approach at different times in their trajectory.

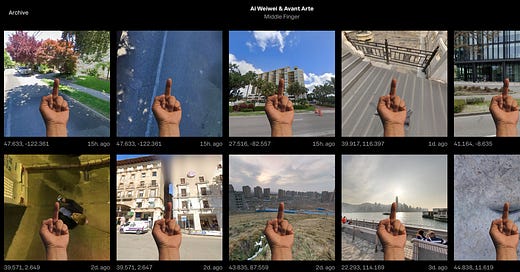

Avant Arte 🎨 With a broad goal of democratizing art and turning Gen Z into a generation of collectors, Avant Arte started from a very personal place. The founders grew up hip-hop obsessed in a small Dutch city lacking a museum. A Kanye album cover sparked their curiosity about the artist George Kondo. They started a Google Docs blog, then an Instagram handle in the early 2010s that accompanied their growing interest in contemporary artists. The “strategy” at the time was little more than producing clever, low-budget deep dives into artists they liked. And that tone and approach quickly attracted fans. But a content business based on the generosity of Meta is a fool’s errand as so many digital publishers have found out. So with no background in the art world, Avant Arte in 2017 started working directly with artists to build a marketplace for their work, with brand storytelling became a crucial part of its early success. Borrowing from streetwear’s drop culture and the scarcity model of luxury brands, they partnered with top name artists to produce limited edition prints and sculptures they would sell on their platform for a short time only. From smaller artists, Avant Arte has gone on to collaborate with luminaries like Ai Wei Wei, Grayson Perry and Judy Chicago, bringing their pedigree to a growing global cadre of print collectors. They built a state-of-the-art printmaking facility in London to control quality, help them scale, and — presumably — increase margins on each piece sold (prices average around €1,500). They do storytelling around that process as well, connecting their customers not just the artist, but the actual process of making the limited edition print that will soon arrive — wonderfully packaged — in their mailboxes. Another competitor in their space treats art collecting more as an investment, offering AI tools to buyers to project their resale value. For Avant Arte, it’s about using stories to nudge people on their collecting journey, and offering the brand as a bridge builder into an opaque and often elitist world. Their content keeps them top of mind even if I haven’t bought anything in a while. And that storytelling is no longer limited to artists, but annual reports filled with data from their community. With this, Avant Arte plays into their broader ambition, serving not just as place to collect, but as a player and influencer in a category (art) that hasn’t yet found the traction of music and fashion, but holds (they hope) serious promise.

Back Market 📠 I find most trending news-related content from brands ill-conceived and cringe-inducing. Back Market’s Pope post yesterday was an exception. They clipped news footage of a clergy member in St. Peter’s Square filming the announcement of the new Pope using a hand-held camcorder, adding a fitting music track and a clever line linking to the Back Market site.

The French company has been building an exceptional platform in second-hand electronics since 2014 under the banner of fighting “planned obsolescence” (here’s a great interview with their co-founder). Most of that work is done in the dark and thankless: sourcing quality resellers, setting up complicated intra-European (and now US) supply chains, device quality verification, repair, customer service … all against a constant tidal ave of “latest and greatest” marketing from Apple and Samsung. It’s the last I want to focus on, because they’ve done such a clever thing by introducing the idea of “fast tech” as a bogeyman for a growing consumer base more mindful of their impact. We’ve been bombarded with sustainability messaging Patagonia took out magazine ads in the 1980s, but it’s only in the last decade that brands — eager to show their doing their best! promise! — have stepped in as well, opening themselves up for (justified) greenwashing criticism and exasperating a consumer base that wants to do good, but often doesn’t know how. Enter Back Market with its call to “End fast tech”, a recent campaign that has stretched from out of home wheat pasting activations into their owned channels and those of their creator partners. This is the strategy of a challenger brand: define a clear opponent and attract a consumer base weary of them. But this ain’t Liquid Death. Back Market isn’t cosplaying sustainability while trying to differentiate itself in a competitive CPG category. They are tapping into a generational desire to lower our consumption, offering affordability in an unsteady economy, and proof of that a circular economy business model can be profitable. And their messaging isn’t always activist in nature. Last Fall, they created a wonderful limited edition capsule collection of upcycled and re-imagined Apple earbuds and Nokia phones with the Montreal-based conceptual artist Gab Bois. And their Innovation Lab head Luiz delivers trustworthy video advice on maintaining your household tech so that you’re not always hunting for an upgrade. It’s a difficult thing to rewire humankind’s desire to accumulate new (and better, always better) things. But Back Market has used tone, creative, and a commitment to its long-term “sabotage” narrative to great effect.

“Because that upgrade ends up in the trash, in a year … or three. And the Next Big Thing is really our soaring carbon footprint.”

— Back«Market